The debate regarding Thatcher and her lasting political impact will carry on over the days and weeks to come. During her 11 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the longest period for any 20th Century British politician, she introduced a number of radical policies and undoubtedly shaped the British economic landscape, for better or worse.

The debate regarding Thatcher and her lasting political impact will carry on over the days and weeks to come. During her 11 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the longest period for any 20th Century British politician, she introduced a number of radical policies and undoubtedly shaped the British economic landscape, for better or worse.

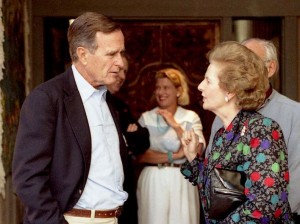

Mrs Thatcher, or ‘Maggie’, polarised voters and was aptly described by her own biographer, John Campbell, as “the most admired, most hated, most idolised and most vilified public figure of the second half of the 20th centuryâ€, but despite strong feelings from the political left against the free-market orientated and monetarist changes she instigated, New Labour continued many of these policies which still live on today.Â

We discuss below some of the areas of greatest impact in the property life and structure of the UK that occurred under the watch of the “Iron Lady”.

The Economical Context

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher inherited the “sick man of Europeâ€, a once great power had been shorn of its empire and was in the economic doldrums. Unemployment was at 1.5 million, net migration over the previous few years had been negative, inflation was in double figures and the once great powerhouse of British manufacturing had declined as a proportion of GDP by 2.95% in the nine years before her appointment.

Britain was widely considered by its international counterparts as a nation in decline and other nations, like West Germany, were performing strongly in comparison

In response, Thatcher set about introducing monetarist policies to control inflation, de-nationalising (privatising) certain industries and instigating social change in the form of property ownership, amongst a myriad of other changes. By the time she departed from British politics in 1992, the UK was undoubtedly a very different place.

Geographical Disparity

British industry and economic success had revolved around London long before Mrs Thatcher came to power, but the importance of manufacturing and mining in the North, Midlands, South Wales and the South West of England had brought wealth and development further afield from the Capital.

International conditions lead to the growth of a global economy, where low labour costs and Government incentives in countries like China made imports cheaper than production at home and made investment overseas increasingly attractive to British companies.

International conditions lead to the growth of a global economy, where low labour costs and Government incentives in countries like China made imports cheaper than production at home and made investment overseas increasingly attractive to British companies.

In Britain, trade union power over wage rates and economic inflation led to rapidly reducing competitiveness in conjunction with what Thatcher saw as the inefficient running of public services. During the ‘Winter of Discontent’ (1978-79) 29,474,000 working days had been lost to strike action – the largest stoppage of work since the 1926 General Strike – severely discouraging investors from choosing Britain.

The National Coal Board in 1983-84 made a loss, subsidised by the Government, of £485 million. Including the subsidy energy companies were forced to pay to assist this industry, that total may have been as high as £727 million a year or £1.4bn in today’s money.

The resulting closures of 97 of Britain’s 174 state-owned mines by 1992 left a number of towns and villages in England and Wales scarred, some to this day, as families that had mined for generations lost their livelihoods. At the same time, the so called ‘Big Bang’ of deregulation and modernisation in the City of London refocused the economy on financial services.

Many forget that this change had already started prior to Mrs Thatcher coming to power. Between 1964 and 1979 Labour closed 326 coalmines, whereas under Mrs Thatcher’s leadership, 154 were closed. In fact, Harold Wilson, Labour Prime Minister between 1964-70 and 1974-76, actually closed more coal mines than Mrs Thatcher. Â

At the same time, the so -called ‘Big Bang’ of deregulation and modernisation in the City of London refocused the economy on financial services.

For British property, this seemingly widened the north-south divide, highlighted in this month’s newsletter. Today, house prices are greatly lower in the north, higher proportions of northern property owners are in negative equity and, whilst London and the South East have proven fairly robust, the north has been deeply affected by the downturn with 50% more unemployment than the south now being the norm. Between June and August 2012 – unemployment in the South East was 6.3%, in the North East it was 9.9%.

Fewer men and women in employment means diminished disposable income in the regional economy. That results in lower savings and greater difficulty accumulating a deposit, coupled with an unwillingness of banks and mortgage companies to part with finance to all but the most reliable of mortgagors. Depressed demand lowers prices and thus the low property values and high unemployment in the North East which we still see now may well be, at least in part, a reflection of the changes Thatcher instigated back in the 1980s.

The Right to Buy

Perhaps the greatest and most apparent change Thatcher made to British property was the Right to Buy scheme which, in its reincarnated form, still remains today.

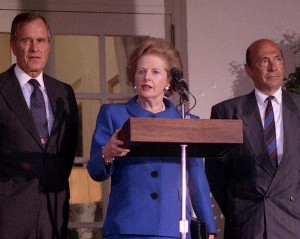

Thatcher Profile  Through the Housing Act 1980, Thatcher’s Conservative Government granted five million council house tenants the ability to purchase the house they lived in at a rate always below the market level and further discounted depending on the length of occupation. A tenant of 20 years could secure their property at a discount of 50% below market value.

Through the Housing Act 1980, Thatcher’s Conservative Government granted five million council house tenants the ability to purchase the house they lived in at a rate always below the market level and further discounted depending on the length of occupation. A tenant of 20 years could secure their property at a discount of 50% below market value.

It is estimated that, up to today, around 2 million council homes have been sold off and the popularity of the scheme has been widely credited with boosting a substantial housing price boom between its introduction and the recession of the early 1990s – perhaps the reason why the Coalition Government reinvigorated the scheme in April 2012.

The “Right to Buy” legacy has been a lasting one and, despite the current slump resulting in home ownership falling to 65% at the end of last year (its lowest level since 1988), most non-property owners still aspire to own their own home.

Mortgage Tax Relief

In 1983, Geoffrey Howe raised the tax allowance from £25,000 to £30,000. Two persons could buy a house together (if unmarried) and both parties were entitled to mortgage tax relief of £30,000 each. i.e. £60,000. This helped significant numbers get on the housing ladder in the 1980’s.   Â

After a sustained period of growth throughout the mid-1980s, the mortgage tax relief rules were changed again in 1988 with disastrous consequences for some; run over by the bandwagon.Â

The original policy granted significant encouragement for people to buy their own homes as raising a deposit was as hard then as it is now. But in the budget of Spring 1988, Nigel Lawson announced ending of the option of pooling allowances and the result was an almost 5 month stampede to try and beat the delayed deadline. It is generally accepted that this rush to beat the deadline helped fuel house price inflation just before the recession and consequentially sparked a painful rebalancing of house prices in the first half of the 1990’s.  Lawson himself acknowledged later that the delay was not his greatest decision.

Changing the face of the Property Market

A number of other changes under the Thatcher Government occurred that we take for granted in the modern day:

Building Societies Act

The Building Societies Act of 1986 opened up the opportunity to offer finance secured against property (mortgages) to the Banks, whereas previously the Building Societies had dominated. Increasing competitiveness kept interest rates low and lending rates high, further fuelling the price bubble which saw house prices rise by 28% in 1988 alone. Â

Income Taxation Factors

Thatcher also left an indelible mark on the British idea of taxation. In 1979, she inherited a top rate of income tax that stood at a staggering 83%. She reduced this to 40% and reduced the bottom rate from 33% to 25%. The higher rate of income tax today still stands at 40%, with an additional rate of 45% for earners of over £150,000.

For property, these lower rates of taxes increased disposable income and arguably have encouraged residential property ownership, whilst increasing the attractiveness of investment in commercial property by ensuring that entrepreneurs may retain more of their hard won earnings.

Social Factors

Interestingly, although Mrs Thatcher stood for family values, divorce rates continued to rise and marriage rates decreased under her prime ministership. This meant more units of accommodation being required with fewer average occupants per house. In conjunction with a rising population through growing immigration and health advances that have extended life expectancies, property demand saw a substantial boost that will have contributed to the house price rises of not only the 1980’s but also the 90s and 00s.

In summary

An article assessing all of Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies that directly or indirectly affected property, their implications and their long-term affects could, and most likely will, cover the pages of a full book.

That said, one thing is readily apparent from the briefest look at the policies she pushed through – for better or worse, Margaret Thatcher changed the landscape of British property and impacted the lives, directly or indirectly, of every one of the United Kingdom’s 63 million inhabitants.

For that, she will be remembered.

08/04/2013Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â SRJ/LCB